I’ve been thinking a great deal about the remarkable jazz trumpeter Frank Newton in the last few weeks, even before having the opportunity to repost this picture of him (originally on JazzWax) — taken in Boston, in the late Forties, with George Wein and Joe Palermino.

I’ve been thinking a great deal about the remarkable jazz trumpeter Frank Newton in the last few weeks, even before having the opportunity to repost this picture of him (originally on JazzWax) — taken in Boston, in the late Forties, with George Wein and Joe Palermino.

Jazz is full of players who say something to us across the years, their instrumental voices resounding through the murk and scrape of old records. Some players seem to have led full artistic lives: Hawkins, Wilson, Milt Hinton, Jo Jones, Bob Wilber come to mind at the head of a long list. Others, equally worthy, have had shorter lives or thwarted careers. Bix, Bird, Brownie, to alliterate, among a hundred others. And all these lives raise the unanswerable question of whether anyone ever entirely fulfills him or herself. Or do we do exactly what we were meant to do, no matter how long our lifespan? Call it Nurture / Nature, free will, what you will.

But today I choose Frank Newton as someone I wish had more time in the sun. His recorded legacy seems both singular and truncated.

Frank Newton (who disliked the “Frankie” on record labels) was born in 1906 in Virginia. He died in 1954, and made his last records in 1946. A selection of the recorded evidence fills two compact discs issued on Jasmine, THE STORY OF A FORGOTTEN JAZZ TRUMPETER.  His Collected Works might run to four or five hours — a brief legacy, and there are only a few examples I know where an extended Newton solo was captured for posterity. However, he made every note count.

His Collected Works might run to four or five hours — a brief legacy, and there are only a few examples I know where an extended Newton solo was captured for posterity. However, he made every note count.

In and out of the recording sudios, he traveled in fast company: the pianists include Willie “the Lion” Smith, James P. Johnson, Teddy Wilson, Sonny White, Mary Lou Williams, Buck Washington, Meade Lux Lewis, Kenny Kersey, Billy Kyle, Don Frye, Albert Ammons, Joe Bushkin, Joe Sullivan, Sonny White, and Johnny Guarneri. Oh, yes — and Art Tatum. Singers? How about Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Maxine Sullivan, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Although Newton first went into the studio with Cecil Scott’s Bright Boys in 1929 for Victor, the brilliant trumpeter Bill Coleman and trombonist Dicky Wells blaze most notably on those sessions.

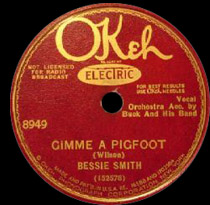

It isn’t until 1933 that we truly hear Newton on record. This interlude, lasting less than a minute, takes place in the middle of Bessie Smith’s “Gimme A Pigfoot,” one of four vaudeville-oriented songs she recorded at her last session, one organized by John Hammond, someone who re-emerges in Newton’s story. It was a magnificent all-star band: Jack Teagarden, Chu Berry, Benny Goodman (for a moment), Buck Washington, guitarist Bobby Johnson, Billy Taylor on bass. Hammond wanted Sidney Catlett on drums, but Bessie refused: “No drums. I set the tempo.” For all the rent-party trappings of the song, “Pigfoot” is thin material, requiring a singer of Bessie’s majesty to make it convincing.

What one first notices about Newton’s solo is his subversive approach, his unusual tone and attack. In 1933, the jazz world was rightly under the spell of Louis, which led to understandable extroversion. Project. Hit those high notes loud. Sing out. If you were accompanying a pop or blues singer, you could stay in the middle register, be part of the background, but aside from such notable exceptions as Joe Smith, Bubber Miley, trumpets were in the main assertive, brassy. Dick Sudhalter thought Newton’s style was the result of technical limitations but I disagree; perhaps Newton was, like Tricky Sam Nanton, painting with sounds.

Before Newton solos on “Pigfoot,” the record has been undeniably Bessie’s, although with murmurings from the other horns and a good deal of Washington’s spattering Hines punctuations. But when Newton enters, it is difficult to remember that anyone else has had the spotlight. Rather than boldly announce his presence with an upwards figure, perhaps a dazzling break, he sidles in, sliding down the scale like a man pretending to be drunk, whispering something we can’t quite figure out, drawling his notes with a great deal of color and amusement, lingering over them, not in a hurry at all. His mid-chorus break is a whimsical merry-go-round up and down figure he particularly liked. It’s almost as if he is teasing us, peeking at us from behind his mask, daring us to understand what he is up to. The solo is the brief unforgettable speech of a great character actor, Franklin Pangborn or Edward Everett Horton, scored for jazz trumpet. Another brassman would have offered heroic ascents, glowing upwards arpeggios; Newton appears to wander down a rock-choked slope, watching his footing. It’s a brilliant gambit: no one could equal Bessie in scope, in power (both expressed and restrained) so Newton hides and reveals, understates. And his many tones! Clouded, muffled, shining for a brief moment and then turning murky, needling, wheedling, guttural, vocal and personal. Considered in retrospect, this solo has a naughty schoolyard insouciance. Given his turn in the spotlight, Newton pretends to thumb his nose at us. Bessie has no trouble taking back the spotlight when she returns, but she wasn’t about to be upstaged by some trumpet-playing boy.

Could any trumpet player, jazz or otherwise, do more than approximate what Newton plays here? Visit http://www.redhotjazz.com/songs/bessie/gimmieapigfoot.ram to hear a fair copy of this recording. (I don’t find that the link works: you may have to go to the Red Hot Jazz website and have the perverse pleasure of using “Pigfoot” as a search term.)

The man who could play such a solo should have been recognized and applauded, although his talent was undeniably subtle. (When you consider that Newton’s place in the John Kirby Sextet was taken by the explosively dramatic Charlie Shavers, Newton’s singularity becomes even clearer.) His peers wanted him on record sessions, and he did record a good deal in the Thirties, several times under his own name. But after 1939, his recording career ebbed and died.

Nat Hentoff has written eloquently of Newton, whom he knew in Boston, and the man who comes through is proud, thoughtful, definite in his opinions, politically sensitive, infuriated by racism and by those who wanted to limit his freedoms. Many jazz musicians are so in love with the music that they ignore everything else, as if playing is their whole life. Newton seems to have felt that there was a world beyond the gig, the record studio, the next chorus. And he was outspoken. That might lead us back to John Hammond.

Hammond did a great deal for jazz, as he himself told us. But his self-portrait as the hot Messiah is not the whole story. Commendably, he believed in his own taste, but he required a high-calorie diet of new enthusiasms to thrive. Hammond’s favorite last week got fired to make way for his newest discovery. Early on Hammond admired Newton, and many of Newton’s Thirties sessions had Hammond behind them. Even if Hammond had nothing to do with a particular record, appearing on one major label made a competing label take notice. But after 1939, Newton never worked for a mainstream record company again, and the records he made in 1944-1946 were done for small independent labels: Savoy (run by the dangerously disreputable Herman Lubinsky) and Asch (the beloved child of the far-left Moses Asch). The wartime recording ban had something to do with this hiatus, but I doubt that it is the sole factor: musicians recorded regularly before the ban. Were I a novelist or playwright, I would invent a scene where Newton rejects Hammond’s controlling patronage . . . and falls from favor, never to return. I admit this is speculation. Perhaps it was simply that Newton chose to play as he felt rather than record what someone else thought he should. A recording studio is often the last place where it is possible to express oneself freely and fully. And I recall a drawing in a small jazz periodical from the late Forties, perhaps Art Hodes’ JAZZ RECORD, of Newton in the basement of an apartment building where he had taken a job as janitor so that he could read, paint, and perhaps play his trumpet in peace.

I think of Django Reinhardt saying, a few weeks before he died, “The guitar bores me.” Did Newton grow tired of his instrument, of the expectations of listeners, record producers, and club-owners? On the rare recording we have of his speaking voice — a brief bit of a Hentoff interview — Newton speaks with sardonic humor about working in a Boston club where the owner’s taste ran to waltzes and “White Christmas,” but using such constraints to his advantage: every time he would play one of the owner’s sentimental favorites, he would be rewarded with a “nice thick steak.” A grown man having to perform to be fed is not a pleasant sight, even though it is a regular event in jazz clubs.

In addition, John Chilton’s biographical sketch of Newton mentions long stints of illness. What opportunities Newton may have missed we cannot know, although he did leave Teddy HIll’s band before its members went to France. It pleases me to imagine him recording with Django Reinhardt and Dicky Wells for the Swing label, settling in Europe to escape the racism in his homeland. In addition, Newton lost everything in a 1948 house fire. And I have read that he became more interested in painting than in jazz. Do any of his paintings survive?

Someone who could have told us a great deal about Newton in his last decade is himself dead — Ruby Braff, who heard him in Boston, admired him greatly and told Jon-Erik Kellso so. And on “Russian Lullaby,” by Mary Lou WIlliams and her Chosen Five (Asch, reissued on vinyl on Folkway), where the front line is bliss: Newton, Vic Dickenson, and Ed Hall, Newton’s solo sounds for all the world like later Ruby — this, in 1944.

In her notes to the Jasmine reissue, Sally-Ann Worsford writes that a “sick, disenchanted, dispirited” Newton “made his final appearance at New York’s Stuyvesant Casino in the early 1950s.” That large hall, peopled by loudly enthusiastic college students shouting for The Saints, would not have been his metier. It is tempting, perhaps easy, to see Newton as a victim. But “sick, disenchanted, dispirited” is never the sound we hear, even on his most mournful blues.

The name Jerry Newman must be added here — and a live 1941 recording that allows us to hear the Newton who astonished other players, on “Lady Be Good” and “Sweet Georgia Brown” in duet with Art Tatum (and the well-meaning but extraneous bassist Ebenezer Paul), uptown in Harlem, after hours, blessedly available on a HighNote CD under Tatum’s name, GOD IS IN THE HOUSE.

Jerry Newman was then a jazz-loving Columbia University student with had a portable disc-cutting recording machine. It must have been heavy and cumbersome, but Newman took his machine uptown and found that the musicians who came to jam (among them Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Hot Lips Page, Don Byas, Thelonious Monk, Joe Guy, Harry Edison, Kenny Clarke, Tiny Grimes, Dick Wilson, Helen Humes) didn’t mind a White college kid making records of their impromptu performances: in fact, they liked to hear the discs of what they had played. (Newman, later on, issued some of this material on his own Esoteric label. Sadly, he committed suicide.) Newman caught Tatum after hours, relaxing, singing the blues — and jousting with Newton. Too much happens on these recordings to write down, but undulating currents of invention, intelligence, play, and power animate every chorus.

On “Lady Be Good,” Newton isn’t in awe of Tatum and leaps in before the first chorus is through, his sound controlled by his mute but recognizable nonetheless. Newton’s first chorus is straightforward, embellished melody with some small harmonic additions, as Tatum is cheerfully bending and testing the chords beneath him. It feels as if Newton is playing obbligato to an extravagantly self-indulgent piano solo . . . . until the end of the second duet chorus, where Newton seems to parody Tatum’s extended chords: “You want to play that way? I’ll show you!” And the performance grows wilder: after the two men mimic one another in close-to-the-ground riffing, Newton lets loose a Dicky Wells-inspired whoop. Another, even more audacious Tatum solo chorus follows, leading into spattering runs and crashing chords. In the out- chorus, Tatum apparently does his best to distract or unsettle Newton, who will not be moved or shaken off. “Sweet Georgia Brown” follows much the same pattern: Tatum wowing the audience, Newton biding his time, playing softly, even conservatively. It’s not hard to imagine him standing by the piano, watching, letting Tatum have his say for three solo choruses that get more heroic as they proceed. When Newton returns, his phrases are climbing, calm, measured — but that calm is only apparent, as he selects from one approach and another, testing them out, taking his time, moving in and outside the chords. As the duet continues, it becomes clear that as forcefully as Tatum is attempting to direct the music, Newton is in charge. It isn’t combat: who, after all, dominated Tatum? But I hear Newton grow from accompanist to colleague to leader. It’s testimony to his persuasive, quiet mastery, his absolute sense of his own rightness of direction (as when he plays a Tatum-pattern before Tatum gets to it). At the end, Newton hasn’t “won” by outplaying Tatum in brilliance or volume, speed or technique — but he has asserted himself memorably.

Taken together, these two perfomances add up to twelve minutes. Perhaps hardly enough time to count for a man’s achievement among the smoke, the clinking glasses, the crowd. But we marvel at them. We celebrate Newton, we mourn his loss.

Postscript: in his autobiography, MYSELF AMONG OTHERS, Wein writes about Newton; Hentoff returns to Newton as a figure crucial in his own development in BOSTON BOY and a number of other places. And then there’s HUNGRY BLUES, Benjamin T. Greenberg’s blog (www.hungryblues.net). His father, Paul Greenberg, knew Newton in the Forties and wrote several brief essays about him — perhaps the best close-ups we have of the man. In Don Peterson’s collection of his father Charles’s resoundingly fine jazz photography, SWING ERA NEW YORK, there’s a picture of Newton, Mezz Mezzrow, and George Wettling at a 1937 jam session. I will have much more to write about Peterson’s photography in a future posting.

Pingback: THE ELUSIVE FRANK NEWTON

Newton’s playing reminds me of a line from Yeats’ “The Song of Wandering Aengus”:

“Through hollow lands and hilly lands…”

It’s not difficult to see how the crudity and lack of respect directed towards jazz musicians in the ’30’s took its toll on such a thoughtful sensitive soul. And how the solitary art of paint must have appealed to him more than the smoke-filled chattering jazz toilets.

I dream of Newton-Monk duets…

One of the glories of jazz playing is that the people on the stand assemble themselves into a synergistic community and at the end of the performance, look at each other happily, pleased and amazed by what they have made. But the spiritual noise they have to get through or transcend to play a meaningful note — the audience, the clubowner, the sticking valve, the person on the stand who doesn’t know that it’s a D9, not D minor — I agree that paint, canvas, brushes, and the mind’s eye might be easier to control . . . . Always a pleasure to hear your words, Pops. Thank you for nearly forty years!

Pingback: Night Lights Classic Jazz Blog and Radio Program with David Brent Johnson | WFIU Public Media

Pingback: Jazz News of Note | Night Lights Classic Jazz - WFIU Public Radio

My aunt who died in 1996 was married to frank. Her name was Ethel Klein newton. I never knew I had an aunt Ethel til my parents divorce In 1961 as she had been head of the communist party in new yOrk and dad was an atomic scientist . Apparently she showed up at the divorce trial with letters from j Edgar Hoover and Bobby Kennedy thanking her for her work as a double agent . That was when I first was allowed to know about her and meet her. I know my mom always told me Frankie was the love of her life.

Pingback: Top 100 Artists of All Time | 100 - 91

Very interesting topic. The FBI File on Frankie should have a treasure trove of information. Frank Newton: Eric Hobsbawm’s favourite jazz musician?

October 4, 2012 at 11:11 pm (black culture, Civil liberties, good people, history, intellectuals, jazz, Jim D, Marxism, music, politics, socialism, stalinism)

The late Eric Hobsbawm wrote about Jazz under the name ‘Francis Newton.’ The use of a pseudonym may have been because he wished to keep his academic work separate from his jazz criticism, and may also have been to do with the Communist Party’s hostility towards jazz in the 1940s and ’50s. But in any case, the choice of that particular name cannot have been a co-incidence: Frank (sometimes “Frankie”) Newton was a fine but neglected black US trumpet player of the 1930′s and 40′s, who was unusual amongst professional jazz musicians of that generation in being politically active. Newton was at the very least, a ‘fellow-traveller’ of the US Communist Party, and was probably a member. The occasion of Hobsbawm’s death seems an appropriate moment to remind (actually, to tell) the world about Frank Newton.

Little has been written about Newton over the years (though Michael Steinman at Jazz Lives and Ben Greenberg at Hungry Blues have posted about him), so I’m re-publishing below, a slightly edited and amended version of the late Sally-Ann Worsfold‘s booklet-notes for the Jasmine double-CD set ‘Frank Newton – The Story Of A Forgotten Jazz Trumpeter’:

“Frank Newton had a special sound…he always believed in giving the people something different,” the trombonist Dicky Wells once observed. Jazz historian Al Rose described Newton as “… an exciting, inventive trumpet player.” Despite such acclaim, the career of one of jazz trumpet’s most individualistic, dynamic stylists has been consigned largely to the footnotes and margins of the music’s history.

During his relatively short life (he died aged 48 in 1954) in a chequered career dogged by frequent bouts of ill health, Frank Newton still managed to record some 150 titles, fifty of which appear on the Jasmine double CD set. He often played in very disinguished company, something which makes his lack of proper recognition all the more puzzling. On various recordings he is to be heard performing alongside Sidney Bechet (see photo above), Pete Brown, Don Byas, Bud Freeman, J.C. Higginbotham, Dicky Wells, James P. Johnson, Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith and Teddy Wilson. He accompanied singers Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith and Maxine Sullivan.

The details of the trumpeter’s early life are very sparse, although it is known he was born in Emory, Virginia, in January 1906 and was christened William Frank Newton. Early professional musical experience included a spell with local band-leader Clarence Paige, then soon after leaving his home state, Newton joined an outfit lead by banjoist/guitarist Elmer Snowden. The trumpeter then joined the Cincinnati based Cecil Scott’s Bright Boys and, during the course of an engagement at New York’s presigious Savoy Ballroom in 1929, made his recording debut with them (‘Bright Boy Blues’).

Bill Coleman was the outfit’s principle trumpet soloist, but Newton held his own with what would become his trademarks: a burnished tone and an audacious bravado in the upper register, combined with a powerfully expressive, blues drenched approach. He could always create the maximum impact with just a few well chosen, judiciously placed notes.

The trombonist in the Scott band, Dicky Wells, another great jazz individualist who later came to prominence with the Count Basie Orchestra of the late 1930′s, remained a friend and occasional colleague of Newton’s over the years. After leaving Scott, they worked together in Charlie Johnson’s Orchestra at Small’s Paradise, a noted Harlem night-spot. From this point, the trumpeter’s career details are hazy, although it is known he had begun broadcasting regularly in in 1932 with the pianist Garland Wilson on the New York radio station WVED. He also participated on a Benny Carter recording session that year.

One year then elapsed before Newton returned to the recording studio in November 1933. The wealthy, influential jazz enterpreneur John Hammond, a great champion of the trumpeter’s work, selected him to play alongside the tenor saxophonist Chu Berry, trombonist Jack Teagarden and clarinettist Benny Goodman, to accompany the great Bessie Smith on what proved to be her final recording session, producing ‘Gimme A Pigfoot’ and ‘Take Me For A Buggy Ride.’

Ill health put Newton’s career on hold for a couple of years at this point, but in March 1936 he returned to the studios as part of a fine band organized by clarinettist Mezz Mezzrow, recording material intended for the jukebox. Newton provides many of the high spots of the session, notably his contribution to ‘The Panic Is On’ where his playing is forward-looking and boppish.

The trumpeter was reunited with his old friend Dicky Wells when he joined the Teddy Hill Orchestra in the spring of 1936, playing some challenging charts with distinctly “modern” overtones. Newton’s work on the band’s records shows him to be a commanding big-band lead without sounding either superficial over over the top.

But fate, it seemed, had decreed Newton to be one of jazz’s ‘nearly’ men: once again incapacity stymied his career. On leaving the Teddy Hill Orchestra, he was succeeded by Dizzy Gillespie for whom the Hill band was, of course, the springboard to fame and fortune. The band also toured Europe where many of its members made recordings (in Paris) that established them as household names amongst European fans: but that was after Newton had departed.

Newton also appeared with the Charlie Barnett Orchestra spasmodically between 1935 and 1937. His presence as an Afican-American in this otherwise white aggregation drew far less attention than Benny Goodman’s employment of pianist Teddy Wilson, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton and guitarist Charlie Christian in various permutations of his small groups. Nevertheless, A souvenir of the trumpeter’s tenure with Barnet is the dazzling record of ‘Emperor Jones.’

In 1937 Newton worked regularly with various small groups in Harlem, often recording with other advanced swing players like altoist Pete Brown, pianist Don Frye and clarinettist Edmond Hall. He also accompanied the vocalist Maxine Sullivan on her big hit ‘Loch Lamond.’ Maxine was married to bassist John Kirby and Newton was a founder member of his highly influential and increasingly popular sextet. But just as the John Kirby Sextet had begun to establish itself as a major 52nd Street attraction at the Onyx Club, a severe back injury forced Newton to quit. With its new trumpet player, Charlie Shavers, the Kirby outfit enjoyed widespread success. Newton’s bad luck had stuck again.

Newton was largely out of action for over a year, but he did manage to participate in a short-lived, racially integrated fifteen-piece band known as the Disciples of Swing, organised by Mezz Mezzrow. In addition to Newton, the brass section boasted fellow trumpeters Sidney de Paris and Max Kaminsky, and trombonists George Lugg and Vernon Brown. The new band was launched at the Harlem Uproar House, a prestigious 52nd Street venue but a racist attack on the premises (the joint was smashed up and daubed with swastikas), combined with bad management and legal wrangles, put paid to a promising and exciting band.

The French jazz writer Hughes Panassie arrived in New York in late 1938 to organise some recording sessions for Victor. For some reason he appointed the eccentric Mezz Mezzrow to round up the musicians. Having recorded some New Orleans-born musicians like Sidney Bechet and the trumpeter Tommy Ladnier, Panassie selected Newton to lead a pick-up group of swing style musicians. Apart from Mezzrow the others included Newton’s long-term associate, the altoist Pete Brown, pianist James P. Johnson and guitarist Al Casey.

The six titles, originally released on the Victor subsidiary Bluebird, combined jazz-friendly standards with originals. All the participants are captured on top form, most especially Newton. His performances on this session cover all facets of his style, from his fiery, trenchent open horn on the up-tempos to his sometimes almost introspective, always lyrical muted vein. Few have equalled his melodic eloquence and profoundly moving blues expression on ‘Blues My Baby Gave To Me’, with its brief nod to the ballad ‘Willow Weep For Me.‘ His exuberant, assertive presence on ‘Rompin’ inspires the others to even greater heights. Even Mezz, not always the sharpest jazz tool in the shed, picks up the momentum to produce one of his better solos.

Newton’s luck seemed to be changing when two exciting opportunities arose simultaneously in the spring of 1939, both of which promised to bring him the acclaim his talent deserved. In early April that year he first recorded for the fledgling Blue Note record company, newly established by Alfred Lion and Francis Wolf as a ‘pure’ jazz operation and already showing every sign of becoming a highly prestigeous label . The other break was perhaps the most important of his career. A former show salesman, Barney Josephson, invited Newton to form a band to launch a new venue, Cafe Society. The club boasted a radical policy: it welcomed both white and African-American patrons. That the place was not tucked away in some obscure backwater but was out and proud in the heart of New York spoke volumes. The trumpeter readily agreed to come onboard and selected altoist Tab Smith, pianist Kenny Kersey and tenorist Kenneth Hollon for the band. Although officially called ’Frank Newton and His Cafe Society Orchestra’, the club’s handbills described him as “Trumpet tootin’ Frankie Newton” and the name Frankie seemed to stick even though he always referred to himself as Frank. Again, the music (judging by the records) was hard-swinging and forward-looking, with Kenny Kersey using dissonant harmonies of the kind later to be associated with Thelonious Monk and Newton himself frequently using boppish phrasing.

Primarily devoted to presenting jazz artists, Cafe Society became a forum to promote left-wing ideals. The choice of Frank Newton to lead the house band was no accident: rare among jazz musicians of his generation, Newton took an active interest in politics and was a committed left winger and Civil Rights campaigner. An impassioned, eloquent spokesman for his beliefs, he loved to engage in debate. A philosopher with an interest in the arts generally, he was also, by all accounts, a talented painter. According to jazz historian Al Rose, Newton’s closest friends were the authors William Sarayon and Henry Miller, who were his near neighbours in Greenwich Village, New York’s ‘bohemian’ quarter.

The Newton band proved versatile in supporting various singers at Cafe Society. Billie Holiday was the first headline act, and contemporary recordings (principally for Milt Gabler’s Commodore label) illustrate how beautifully her voice was complemented by the Newton group. One of these sides, ‘Strange Fruit,’ proved to be a significant landmark in Lady Day’s career. Originally a poem written by Lewis Allen, then set to music, the song was brought to Billie’s attention at Cafe Society, conceivably by Frank Newton himself. An anti-lynching protest song, it was unlike anything Billie had recorded before. Initially wary of the contoversy it might cause, Billie then realised its sentiments should be widely heard.

On a darkened stage, with just her face bathed in a potlight, Billie began to perform ‘Strange Fruit’ as her closing number each night at Cafe Society – to have followed it up with a ballad or lightweight love song would have been incongruous. Billie wanted to record it but her label, American Columbia, refused. Columbia did, however, permit her to record it for the small Commodore label. The recording adheres to her stage presentation: Newton’s sombre, stark introduction gives way to the plaintively sparse piano chords from Sonny White, the singer’s regular accompanist. Billie then occupies centre stage to deliver her message without any further instrumental breaks or vocal reprise. The number remained in her repertoire for the rest of her life.

Newton’s associations with both Blue Note and Cafe Society were abruptly ended after just four months, probably because of his recurring health problems. By 1940, sufficiently recuperated, he formed a band with old friend Pete Brown at the New York club Kelly’s Stables. He also worked briefly with Sidney Bechet at Camp Unity in New York State, a holiday resort devoted to promoting racial harmony. Later, Newton moved to Boston where he worked in a band with another old sidekick, Ed Hall.

Five years after his last Blue Note recording, Newton returned to the studios – Savoy, this time – with an all-star band including Teddy Wilson, Red Norvo and Don Byas in 1944. Newton was, as usual on recordings, in excellent form, but the records did little to rescue him from obscurity.

There were to be just a handful more recordings added to Newton’s discography, including some with pianist Mary Lou Williams and a date featuring singer Albinia Jones on which he was teamed with Dizzy Gillespie. In addition to failing health, a fire at Newton’s home in 1948 claimed all his possessions, including his trumpet. Sick, disenchanted and dispirited, he made his final appearance at New York’s Stuyvesant Casino in the early 1950′s.

Frank Newton died aged 48 in November 1954. Despite prolonged ill health and many bad breaks, Frank Newton firmly secured his place in the pantheon of great jazz trumpeters.

Sally-Ann Worsfold, August 2002 (adapted/edited by Jim Denham).

Pingback: Hot Jazz Meets (the) Gospel, Just In Time for Halloween | The Pop of Yestercentury

I know this article is a several years old. I too have been researching and looking into the life of Frankie Newton. My great grandfather (Thomas Newton) was his older brother and my late grandfather (William Newton) was his nephew. I have bought several albums of his through various sellers on ebay. Any additional information on his life would be helpful in my family history research.

Pingback: Jazz of Physics – JHO2

Pingback: Frank Newton, jazz trumpeter and left-wing activist – Shiraz Socialist (Second Run)

In an Aug 28, 1925 Zanesville, Ohio newspaper in the “Colored Citizens News” column it states

Clarence Paige’s Ten Kings of the Ballroom of Cincinnati will play a one – week engagement in Zanesville.

Would you furnish any further information about Clarence Paige, please?

Possibly I don’t know anything out of the ordinary, but I will ask my more erudite friends. What, if I might ask, is your connection to Clarence Paige and Frank Newton? Thanks, Michael