Between 1953 and 1957, John Hammond supervised a series of record dates for the Vanguard label. I first heard one of those records — the second volume of the THE VIC DICKENSON SHOWCASE — at my local library in the late Sixties, and fell in love.

The Vanguard sessions featured Ruby Braff, Shad Collins, Buck Clayton, Joe Newman, Emmett Berry, Pat Jenkins, Doug Mettome, Vic Dickenson, Benny Morton, Benny Green, Urbie Green, Lawrence Brown, Henderson Chambers, Ed Hall, Peanuts Hucko, Jimmy Buffington, Coleman Hawkins, Buddy Tate, Rudy Powell, Earle Warren, Lucky Thompson, Frank Wess, Pete Brown, Paul Quinichette, Mel Powell, Sir Charles Thompson, Jimmy Jones, Hank Jones, Sammy Price, Ellis Larkins, Nat Pierce, Steve Jordan, Skeeter Best, Kenny Burrell, Oscar Pettiford, Walter Page, Aaron Bell, Jo Jones, Bobby Donaldson, Jimmy Crawford, Jimmy Rushing, and others.

The list of artists above would be one answer to the question, “What made these sessions special?” but we all know of recordings with glorious personnel that don’t quite come together as art — perhaps there’s too little or too much arranging, or the recorded sound is not quite right, or one musician (a thudding drummer, an over-amplified bassist) throws everything off.

The Vanguard sessions benefited immensely from Hammond’s imagination. Although I have been severe about Hammond — as someone who interfered with musicians for whom he was offering support — and required that his preferences be taken seriously or else (strong-willed artists like Louis, Duke, and Frank Newton fought with or ran away from John). Hammond may have been “difficult” and more, but his taste in jazz was impeccable. And broad — the list above goes back to Sammy Price, Walter Page, and forward to Kenny Burrell and Benny Green.

Later on, what I see as Hammond’s desire for strong flavors and novelty led him to champion Dylan and Springsteen, but I suspect that those choices were also in part because he could not endure watching others make “discoveries.” Had it been possible to continue making records like the Vanguards eternally, I believe Hammond might have done so.

Although Mainstream jazz was still part of the American cultural landscape in the early Fifties, and the artists Hammond loved were recording for labels large and small — from Verve, Columbia, Decca, all the way down to Urania and Period — he felt strongly about players both strong and subtle, musicians who had fewer opportunities to record sessions on their own. At one point, Hammond and George Wein seemed to be in a friendly struggle to champion Ruby Braff, and I think Hammond was the most fervent advocate Vic Dickenson, Sir Charles Thompson, and Mel Powell ever had. Other record producers, such as the astute George Avakian at Columbia, would record Jimmy Rushing, but who else was eager to record Pete Brown, Shad Collins, or Henderson Chambers? No one but Hammond.

And he arranged musicians in novel — but not self-consciously so — combinations. For THE VIC DICKENSON SHOWCASE, it did not take a leap of faith to put Braff, Vic, and Ed Hall together in the studio, for they had played together at Boston’s Savoy Cafe in 1949. And to encourage them to stretch out for leisurely versions of “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now,” “Jeepers Creepers,” and “Russian Lullaby” was something that other record producers — notably Norman Granz — had been doing to capitalize on the longer playing time of the new recording format. But after that rather formal beginning, Hammond began to be more playful. The second SHOWCASE featured Shad Collins, the masterful and idiosyncratic ex-Basie trumpeter, in the lead, with Braff joining in as a guest star on two tracks.

Now, some of the finest jazz recordings were made in adverse circumstances (I think of the cramped Brunswick and Decca studios of the Thirties). And marvelous music can be captured in less-than-ideal sound: consider Jerry Newman’s irreplaceable uptown recordings. But the sound of the studio has a good deal to do with the eventual result. Victor had, at one point, a converted church in Camden, New Jersey; Columbia had Liederkrantz Hall and its 30th Street Studios. Hammond had a Masonic Temple on Clermont Avenue in Brooklyn, New York — with a thirty-five foot ceiling, wood floors, and beautiful natural resonance.

The Vanguard label, formed by brothers Maynard and Seymour Solomon, had devoted itself to beautiful-sounding classical recordings; Hammond had written a piece about the terrible sound of current jazz recordings, and the Solomons asked him if he would like to produce sessions for them. Always eager for an opportunity to showcase musicians he loved, without interference, Hammond began by featuring Vic Dickenson, whose sound may never have been as beautifully captured as it was on the Vanguards.

Striving for an entirely natural sound, the Vanguards were recorded with one microphone hanging from the ceiling. The players in the Masonic Temple did not know what the future would hold — musicians isolated behind baffles, listening to their colleagues through headphones — but having one microphone would have been reminiscent of the great sessions of the Thirties and Forties. And musicians often become tense at recording sessions, no matter how professional or experienced they are — having a minimum of engineering-interference can only have added to the relaxed atmosphere in the room.

The one drawback of the Masonic Temple was that loud drumming was a problem: I assume the sound ricocheted around the room. So for most of these sessions, either Jo Jones or Bobby Donaldson played wire brushes or the hi-hat cymbal, with wonderful results. (On the second Vic SHOWCASE, Jo’s rimshots explode like artillery fire on RUNNIN’ WILD, most happily, and Jo also was able to record his lengthy CARAVAN solo, so perhaps the difficulty was taken care of early.) On THE NAT PIERCE BANDSTAND — a session recently reissued on Fresh Sound — you can hear the lovely, translucent sound Freddie Green, Walter Page, and Jo Jones made, their notes forming three-dimensional sculpture on BLUES YET? and STOMP IT OFF.

(Something for the eyes. I am not sure what contemporary art directors would make of this cover, including Vic’s socks, and the stuffed animals, but I treasure it, even though there is a lion playing a concertina.)

(Something for the eyes. I am not sure what contemporary art directors would make of this cover, including Vic’s socks, and the stuffed animals, but I treasure it, even though there is a lion playing a concertina.)

What accounted for the beauty of these recordings might be beyond definition. Were the musicians so happy to be left alone that they played better than ever? Was it the magisterial beat and presence of Walter Page on many sessions? Was it Hammond’s insistence on unamplified rhythm guitar? Whatever it was, I hear these musicians reach into those mystical spaces inside themselves with irreplaceable results. On these recordings, there is none of the reaching-for-a-climax audible on many records. Nowhere is this more apparent than on the sessions featuring Ruby Braff and Ellis Larkins. Braff had heard Larkins play duets with Ella Fitzgerald for Decca (reissued on CD as PURE ELLA) and told Hammond that he, too, wanted to play with Larkins. Larkins’ steady, calm carpet of sounds balances Braff’s tendency towards self-dramatization, especially on several Bing Crosby songs — PLEASE and I’VE GOT A POCKETFUL OF DREAMS.

Ruby and Ellis were reunited several times in the next decades, for Hank O’Neal’s Chiaroscuro label and twice for Arbors, as well as onstage at a Braff-organized tribute to Billie Holiday, but they never sounded so poignantly wonderful as on the Vanguards.

Hammond may have gotten his greatest pleasure from the Basie band of the late Thirties, especially the small-group sessions, so he attempted to give the Vanguards the same floating swing, using pianists Thompson and Pierce, who understood what Basie had done without copying it note for note. For THE JO JONES SPECIAL, Hammond even managed to reunite the original “All-American Rhythm Section” for two versions of “Shoe Shine Boy.” Thompson — still with us at 91 — recorded with Walter Page, Freddie Green, and Jo Jones for an imperishable quartet session. If you asked me to define what swing is, I might offer their “Swingtime in the Rockies” as compact, enthralling evidence.

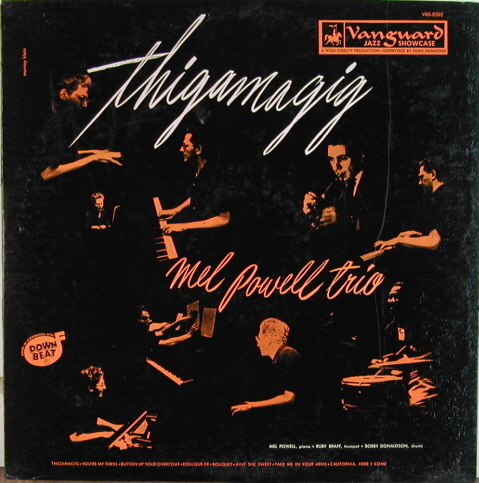

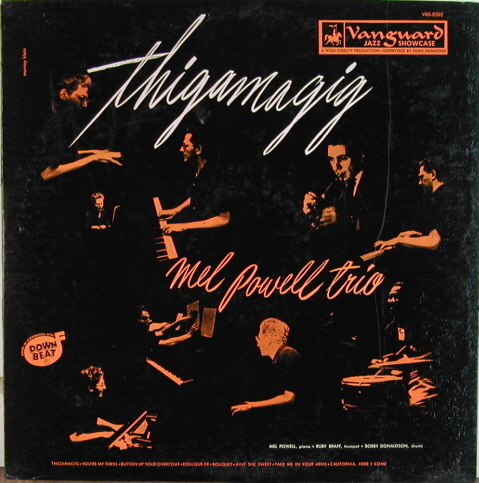

Hammond was also justifiably enthusiastic about pianist Mel Powell — someone immediately identifiable in a few bars, his style merging Waller, Tatum, astonishing technique, sophisticated harmonies, and an irrepressible swing — and encouraged him to record in trios with Braff, with Paul Quinichette, with Clayton and Ed Hall, among others. One priceless yet too brief performance is Powell’s WHEN DID YOU LEAVE HEAVEN? with French hornist Jimmy Buffington in the lead — a spectral imagining of the Benny Goodman Trio.

The last Vanguards were recorded in 1957, beautiful sessions featuring Buck Clayton and Jimmy Rushing. I don’t know what made the series conclude. Did the recordings not sell well? Vanguard turned to the burgeoning folk movement shortly after. Or was it that Hammond had embarked on this project for a minimal salary and no royalties and, even given his early patrician background, had to make a living? But these are my idea of what jazz recordings should sound like, for their musicality and the naturalness of their sound.

I would like to be able to end this paean to the Vanguards by announcing a new Mosaic box set containing all of them. But I can’t. And it seems as if forces have always made these recordings difficult to obtain in their original state. Originally, they were issued on ten-inch long-playing records (the format that record companies thought 78 rpm record buyers, or their furniture, would adapt to most easily). But they made the transition to the standard twelve-inch format easily. The original Vanguard records didn’t stay in print for long in their original format. I paid twenty-five dollars, then a great deal of money, for a vinyl copy of BUCK MEETS RUBY from the now-departed Dayton’s Records on Twelfth Street in Manhattan. In the Seventies, several of the artists with bigger names, Clayton, Jo Jones, and Vic, had their sessions reissued in America on two-lp colletions called THE ESSENTIAL. And the original vinyl sessions were reissued on UK issues for a few minutes in that decade.

When compact discs replaced vinyl, no one had any emotional allegiance to the Vanguards, although they were available in their original formats (at high prices) in Japan. The Vanguard catalogue was bought by the Welk Music Group (the corporate embodiment of Champagne Music). in 1999, thirteen compact discs emerged: three by Braff, two by “the Basie Bunch,” two by Mel Powell, two by Jimmy Rushing, one by Sir Charles, one by Vic. On the back cover of the CDs, the credits read: “Compilation produced by Steve Buckingham” and “Musical consultant and notes by Samuel Charters.” I don’t know either of them personally, and I assume that their choices were controlled by the time a compact disc allows, but the results are sometimes inexplicable. The sound of the original sessions comes through clearly but sessions are scrambled and incomplete, except for the Braff-Larkins material, which they properly saw as untouchable. And rightly so. The Vanguard recordings are glorious. And they deserve better presentation than they’ve received.

P.S. Researching this post, I went to the usual sources — Amazon and eBay — and there’s no balm for the weary or the deprived. On eBay, a vinyl BUCK MEETS RUBY is selling for five times as much. That may be my twenty-five dollars, adjusted for inflation, but it still seems exorbitant.

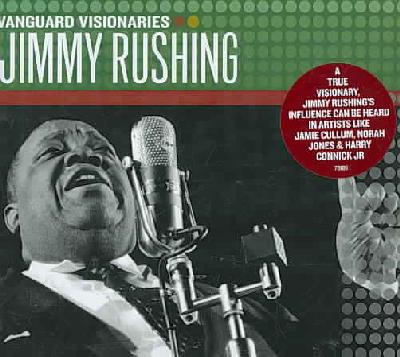

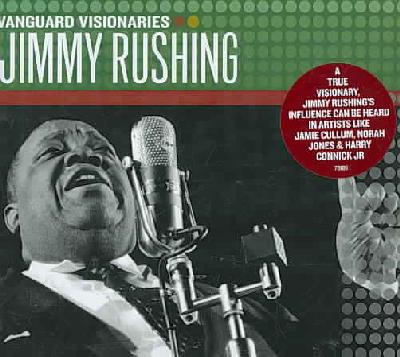

On eBay I also saw the most recent evidence of the corruption, if not The Decline, of the West. Feast your eyes on this CD cover:

Can you imagine Jimmy Rushing’s reaction — beyond the grave — on learning that his reputation rested on his being an influence on Jamie Cullum, Norah Jones, and Harry Connick, Jr.? I can’t. The Marketing Department has been at work! But I’d put up with such foolishness if I could have the Vanguards back again.

(Something for the eyes. I am not sure what contemporary art directors would make of this cover, including Vic’s socks, and the stuffed animals, but I treasure it, even though there is a lion playing a concertina.)

(Something for the eyes. I am not sure what contemporary art directors would make of this cover, including Vic’s socks, and the stuffed animals, but I treasure it, even though there is a lion playing a concertina.)