It all goes back to my father, who loved music and was intrigued by the technology of his time. We had a Revere reel-to-reel tape recorder when I was a child, and I, too, was fascinated.

I could put on a tape and hear his voice coming out of the speaker; I could record myself playing the accordion; I could tape-record a record a friend owned. Recording music and voices ran parallel to my early interest (or blossoming obsession) with jazz.

I realized that when I saw Louis Armstrong on television (in 1967, he appeared with Herb Alpert and the Tia Juana Brass) I could connect the tape recorder and have an audio artifact — precious — to be revisited at my leisure.

I knew that my favorite books and records could be replayed; why not “real-time performances”? At about the same time, my father brought home a new toy, a cassette player. Now I could tape-record my favorite records and bring them on car trips; my sister and her husband could send us taped letters while on vacation in Mexico.

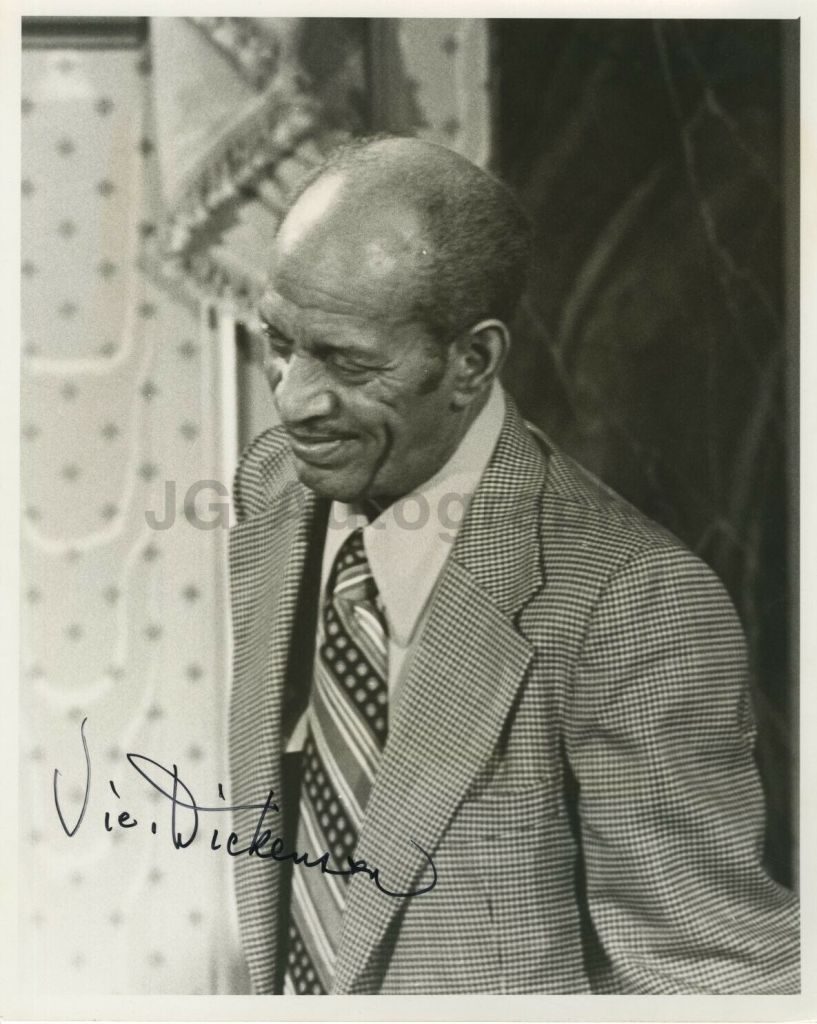

In 1969, I had the opportunity to venture into New York City for my first live jazz concert (after seeing Louis and the All Stars in 1967). I think the concert was a Dick Gibson extravaganza with The World’s Greatest Jazz Band (Eddie Hubble and Vic Dickenson on trombones) and a small group of Zoot and Al, Joe Newman, a trombonist, and a rhythm section. Gibson told the story of THE WHITE DEER in between sets.

I had a wonderful time. But I also made my first foray into criminality. In a bright blue airline bag I brought and hid that very same cassette recorder and taped the concert. (I no longer have the tapes. Alas. Zoot and Al played MOTORING ALONG and THE RED DOOR; the WGJB rocked and hollered gorgrously.)

I brought the same recorder to a concert at Queens College, capturing Ray Nance, Newman, Garnett Brown, Herb Hall, Hank Jones, Milt Hinton, and Al Foster . . . names to conjure with for sure. And from that point on, when I went to hear jazz, I brought some machinery with me. Occasionally I borrowed another recorder (my friend Stu had a Tandberg) or I brought my own heavy Teac reel-to-reel for special occasions.

Most of the musicians were either politely resigned to the spectacle of a nervous, worshipful college student who wanted nothing more than to make sure their beautiful music didn’t vanish. Joe Thomas was concerned that the union man was going to come along. Kenny Davern briefly yet politely explained that I hadn’t set the microphone up properly, then showed me what would work.

I can recall two players becoming vigorously exercised at the sight of a microphone and either miming (Dicky Wells) or saying (Cyril Haynes) NO . . . and Wild Bill Davison tried to strike a bargain: “You want to tape me?” “Yes, Mister Davison.” “Well, that’ll be one Scotch now and one for each set you want to tape.” My budget wasn’t large, so I put the recorder away.

Proceedingly happily along this path, I made tape recordings of many musicians betwen 1969 and 1982, and traded tapes with other collectors. And those tapes made what otherwise would have been lost in time permanent; we could revisit past joys in the present.

Early in this century, I began to notice that everyone around me seemed to have a video camera. Grandparents were videoing the infants on the rug; lovers were capturing each other (in a nice way) on the subway platform. I thought, “Why can’t I do this with the music?” I started my own YouTube channel in 2006, eighteen months before JAZZ LIVES saw the light.

I had purchased first a Flip camera (easy, portable, with poor video) and then a mini-DVD Sony camera. At the New York traditional-jazz hangout, the Cajun, and elsewhere, I video-recorded the people I admired. They understood my love for the music and that I wasn’t making a profit: Barbara Rosene, Joel Forrester, John Gill, Kevin Dorn, Jon-Erik Kellso, Craig Ventresco, and many others.

If my recording made musicians uncomfortable, they didn’t show it. Fewer than five players or singers have flatly said NO — politely — to me.

Some of the good-humored acceptance I would like to say is the result of my great enthusiasm and joy in the music. I have not attempted to make money for myself on what I have recorded; I have not made the best videos into a private DVD for profit.

More pragmatic people might say, “Look, Michael, you were reviewing X’s new CD in THE MISSISSIPPI RAG or CADENCE; you wrote liner notes for a major record label. X knew it was good business to be nice to you.” I am not so naive as to discount this explanation. And some musicians, seeing the attention I paid to the Kinky Boys or the Cornettinas, might have wanted some of the same for themselves. Even the sometimes irascible couple who ran the Cajun saw my appearances there with camera as good publicity and paid me in dubious cuisine.

The Flip videos were muzzy; the mini-DVDs impossible to transfer successfully to YouTube, so when I began JAZZ LIVES I knew I had to have a better camera, which I obtained. It didn’t do terribly well in the darkness of The Ear Inn, but Jon-Erik Kellso and Matt Munisteri and their friends put up with me and the little red light in the darkness. Vince Giordano never said anything negative.

I began to expand my reach so much so that some people at a jazz party or concert would not recognize me without a camera in front of my face.

The video camera and the jazz blog go together well. I used to “trade tapes” with other collectors, and if I came to see you, I brought some Private Stock as a gift. Now, that paradigm has changed, because what I capture I put on the blog. Everything good is here. It saves me the time and expense of dubbing cassettes or CDs and putting them in mailers, and it’s also nearly instantaneous: if I didn’t care about sleep (and I do) I could probably send video from the Monday night gig around the world on Tuesday afternoon. Notice also that I have written “around the world.”

The video camera has made it possible for me to show jazz lovers in Sweden what glorious things happen at The Ear Inn or at Jazz at Chautauqua; my dear friends whom I’ve never met in person in Illinois and Michigan now know about the Reynolds Brothers; Stompy Jones can hear Becky Kilgore sing without leaving his Toronto eyrie . . . and so on.

Doing this, I have found my life-purpose and have achieved a goal: spreading joy to people who might be less able to get their fair share. Some of JAZZ LIVES’ most fervent followers have poorer health and less freedom than I do. And these viewers and listeners are hugely, gratifyingly grateful. I get hugged by people I’ve never seen before when I come to a new jazz party.

And I hug back. Knowing that there are real people on the other end of the imaginary string is a deep pleasure indeed.

There are exceptions, of course: the anonymous people who write grudging comments on YouTube about crowd sounds; the viewers who nearly insist that I drop everything and come video the XYZ Wrigglers because they can’t make it; the Corrections Officers who point out errors in detail, fact, or what they see as lapses of taste; the people who say “I see the same people over and over on your blog.” I don’t know.

Had I done nothing beyond making more people aware of the Reynolds Brothers or the EarRegulars, I would think I had not lived in vain. And that’s no stage joke.

But the process of my attempting to spread joy through the musical efforts of my heroes is not without its complexities, perhaps sadness.

If, in my neighborhood, I help you carry your groceries down the street to your apartment because they’re heavy and I see you’re struggling, I do it for love, and I would turn away a dollar or two offered to me. But when I work I expect to get paid unless other circumstances are in play. And I know the musicians I love feel the same way.

The musicians who allow (and even encourage) me to video-record them, to post the results on JAZZ LIVES and YouTube know that I cannot write them a check at union rates for this. I can and do put more money in the tip jar, and I have bought some of my friends the occasional organic burger on brioche. But there is no way I could pay the musicians a fraction of what their brilliant labors are worth — the thirty years of practice and diligence that it took to make that cornet sound so golden, to teach a singer to touch our hearts.

I would have to be immensely wealthy to pay back the musicians I record in any meaningful way. And one can say, “They are getting free publicity,” which is in some superficial way undeniable.

But they are also donating their services for free — for the love of jazz — because the landscape has shifted so in the past decade. They know it and I know it. When I was illicitly tape-recording in Carngie Hall in 1974, I could guess that there were other “tapers” in the audience but they were wisely invisible.

At a jazz party, the air is often thick with video cameras or iPhones, and people no longer have any awareness of how strange that is to the musicians. I have seen a young man lie nearly on his back (on the floor in front of the bandstand) and aim his lighted camera up at a musician who was playing until the player asked him to stop doing that. The young man was startled. In the audience, we looked at each other sadly and with astonishment.

I started writing this post because I thought, not for the first time, “How many musicians who allow me to video them for free would really rather that I did not do it?” I can imagine the phrase “theft of services” floating in the air, unspoken.

Some musicians may let me do what I do because they need the publicity; they live in the hope that a promoter or club booker will see the most recent video on YouTube and offer them a gig. But they’d really rather get paid (as would I) and be able to control the environment (as would I). Imagine, if you will, that someone with a video camera follows you around at work, recording what you do, how you speak. “Is that spinach between my teeth? Do I say “you know” all the time, really? Did you catch me at a loss for words?”

Musicians are of course performers, working in public for pay. And they always have the option to say, “I’m sorry, I don’t want to be videoed. Thank you!” I have reached arrangements — friendly ones — with some splendid musicians — that they will get to see what I have recorded and approve of it before I post it. If they dislike the performance, it never becomes public. And that is perfectly valid. I don’t feel hurt that the musicians “don’t trust [Michael’s] taste,” because Michael is an experienced listener and at best an amateur musician.

But I sometimes feel uncomfortable with the situation I have created. Wanting to preserve the delicate moment — a solo on STARDUST that made me cry, a romping TIGER RAG that made me feel that Joy was surrounding me in the best possible way — I may have imposed myself on people, artists, who weren’t in a position, or so they felt, to ask me to put the camera away. I wonder often if the proliferation of free videos has interfered with what Hot Lips Page called his “livelihood.” I would be very very grieved to think I was cutting into the incomes of the players and singers who have done so much for me.

Were musicians were happier to see me when I was simply an anonymous, eager, nervous fan, asking, “Mr. Hackett, would you sign my record?” Then, in 1974, there was no thought of commerce, no thought of “I loused up the second bar of the third chorus and now it’s going on YouTube and it will stay there forever!”

I can’t speak for the musicians. Perhaps I have already presumed overmuch to do so. I embarked on this endeavor because I thought it was heartbreaking that the music I love disappeared into memory when the set was over.

But I hope I am exploiting no one, hurting no one’s feelings, making no one feel trapped by a smiling man in an aloha shirt with an HD camera.

I don’t plan to put the camera down unless someone asks me to do so. And, to the musicians reading this posting — if I have ever captured a performance of yours on YouTube and it makes you cringe, please let me know and I will make it disappear. I promise. I’ve done that several times, and although I was sorry to make the music vanish, I was relieved that any unhappiness I had caused could be healed, a wrong made right. After all, the music brings such joy to me, to the viewers, and often to the musicians creating it, they surely should have their work made as joyous as possible.

I dream of a world where artists are valued for the remarkable things they give us.

And I think, “Perhaps after I am dead, the sound waves captured by these videos will reverberate through the wide cosmos, making it gently and sweetly vibrate in the best way.” To think that I had made pieces of the music immortal merely by standing in the right place with my camera would make me very happy.

And to the players, I Revere you all.

May your happiness increase.