I’ve been thinking a great deal about the remarkable jazz trumpeter Frank Newton in the last few weeks, even before having the opportunity to repost this picture of him (originally on JazzWax) — taken in Boston, in the late Forties, with George Wein and Joe Palermino.

I’ve been thinking a great deal about the remarkable jazz trumpeter Frank Newton in the last few weeks, even before having the opportunity to repost this picture of him (originally on JazzWax) — taken in Boston, in the late Forties, with George Wein and Joe Palermino.

Jazz is full of players who say something to us across the years, their instrumental voices resounding through the murk and scrape of old records. Some players seem to have led full artistic lives: Hawkins, Wilson, Milt Hinton, Jo Jones, Bob Wilber come to mind at the head of a long list. Others, equally worthy, have had shorter lives or thwarted careers. Bix, Bird, Brownie, to alliterate, among a hundred others. And all these lives raise the unanswerable question of whether anyone ever entirely fulfills him or herself. Or do we do exactly what we were meant to do, no matter how long our lifespan? Call it Nurture / Nature, free will, what you will.

But today I choose Frank Newton as someone I wish had more time in the sun. His recorded legacy seems both singular and truncated.

Frank Newton (who disliked the “Frankie” on record labels) was born in 1906 in Virginia. He died in 1954, and made his last records in 1946. A selection of the recorded evidence fills two compact discs issued on Jasmine, THE STORY OF A FORGOTTEN JAZZ TRUMPETER.  His Collected Works might run to four or five hours — a brief legacy, and there are only a few examples I know where an extended Newton solo was captured for posterity. However, he made every note count.

His Collected Works might run to four or five hours — a brief legacy, and there are only a few examples I know where an extended Newton solo was captured for posterity. However, he made every note count.

In and out of the recording sudios, he traveled in fast company: the pianists include Willie “the Lion” Smith, James P. Johnson, Teddy Wilson, Sonny White, Mary Lou Williams, Buck Washington, Meade Lux Lewis, Kenny Kersey, Billy Kyle, Don Frye, Albert Ammons, Joe Bushkin, Joe Sullivan, Sonny White, and Johnny Guarneri. Oh, yes — and Art Tatum. Singers? How about Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Maxine Sullivan, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Although Newton first went into the studio with Cecil Scott’s Bright Boys in 1929 for Victor, the brilliant trumpeter Bill Coleman and trombonist Dicky Wells blaze most notably on those sessions.

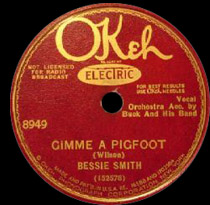

It isn’t until 1933 that we truly hear Newton on record. This interlude, lasting less than a minute, takes place in the middle of Bessie Smith’s “Gimme A Pigfoot,” one of four vaudeville-oriented songs she recorded at her last session, one organized by John Hammond, someone who re-emerges in Newton’s story. It was a magnificent all-star band: Jack Teagarden, Chu Berry, Benny Goodman (for a moment), Buck Washington, guitarist Bobby Johnson, Billy Taylor on bass. Hammond wanted Sidney Catlett on drums, but Bessie refused: “No drums. I set the tempo.” For all the rent-party trappings of the song, “Pigfoot” is thin material, requiring a singer of Bessie’s majesty to make it convincing.

What one first notices about Newton’s solo is his subversive approach, his unusual tone and attack. In 1933, the jazz world was rightly under the spell of Louis, which led to understandable extroversion. Project. Hit those high notes loud. Sing out. If you were accompanying a pop or blues singer, you could stay in the middle register, be part of the background, but aside from such notable exceptions as Joe Smith, Bubber Miley, trumpets were in the main assertive, brassy. Dick Sudhalter thought Newton’s style was the result of technical limitations but I disagree; perhaps Newton was, like Tricky Sam Nanton, painting with sounds.

Before Newton solos on “Pigfoot,” the record has been undeniably Bessie’s, although with murmurings from the other horns and a good deal of Washington’s spattering Hines punctuations. But when Newton enters, it is difficult to remember that anyone else has had the spotlight. Rather than boldly announce his presence with an upwards figure, perhaps a dazzling break, he sidles in, sliding down the scale like a man pretending to be drunk, whispering something we can’t quite figure out, drawling his notes with a great deal of color and amusement, lingering over them, not in a hurry at all. His mid-chorus break is a whimsical merry-go-round up and down figure he particularly liked. It’s almost as if he is teasing us, peeking at us from behind his mask, daring us to understand what he is up to. The solo is the brief unforgettable speech of a great character actor, Franklin Pangborn or Edward Everett Horton, scored for jazz trumpet. Another brassman would have offered heroic ascents, glowing upwards arpeggios; Newton appears to wander down a rock-choked slope, watching his footing. It’s a brilliant gambit: no one could equal Bessie in scope, in power (both expressed and restrained) so Newton hides and reveals, understates. And his many tones! Clouded, muffled, shining for a brief moment and then turning murky, needling, wheedling, guttural, vocal and personal. Considered in retrospect, this solo has a naughty schoolyard insouciance. Given his turn in the spotlight, Newton pretends to thumb his nose at us. Bessie has no trouble taking back the spotlight when she returns, but she wasn’t about to be upstaged by some trumpet-playing boy.

Could any trumpet player, jazz or otherwise, do more than approximate what Newton plays here? Visit http://www.redhotjazz.com/songs/bessie/gimmieapigfoot.ram to hear a fair copy of this recording. (I don’t find that the link works: you may have to go to the Red Hot Jazz website and have the perverse pleasure of using “Pigfoot” as a search term.)

The man who could play such a solo should have been recognized and applauded, although his talent was undeniably subtle. (When you consider that Newton’s place in the John Kirby Sextet was taken by the explosively dramatic Charlie Shavers, Newton’s singularity becomes even clearer.) His peers wanted him on record sessions, and he did record a good deal in the Thirties, several times under his own name. But after 1939, his recording career ebbed and died.

Nat Hentoff has written eloquently of Newton, whom he knew in Boston, and the man who comes through is proud, thoughtful, definite in his opinions, politically sensitive, infuriated by racism and by those who wanted to limit his freedoms. Many jazz musicians are so in love with the music that they ignore everything else, as if playing is their whole life. Newton seems to have felt that there was a world beyond the gig, the record studio, the next chorus. And he was outspoken. That might lead us back to John Hammond.

Hammond did a great deal for jazz, as he himself told us. But his self-portrait as the hot Messiah is not the whole story. Commendably, he believed in his own taste, but he required a high-calorie diet of new enthusiasms to thrive. Hammond’s favorite last week got fired to make way for his newest discovery. Early on Hammond admired Newton, and many of Newton’s Thirties sessions had Hammond behind them. Even if Hammond had nothing to do with a particular record, appearing on one major label made a competing label take notice. But after 1939, Newton never worked for a mainstream record company again, and the records he made in 1944-1946 were done for small independent labels: Savoy (run by the dangerously disreputable Herman Lubinsky) and Asch (the beloved child of the far-left Moses Asch). The wartime recording ban had something to do with this hiatus, but I doubt that it is the sole factor: musicians recorded regularly before the ban. Were I a novelist or playwright, I would invent a scene where Newton rejects Hammond’s controlling patronage . . . and falls from favor, never to return. I admit this is speculation. Perhaps it was simply that Newton chose to play as he felt rather than record what someone else thought he should. A recording studio is often the last place where it is possible to express oneself freely and fully. And I recall a drawing in a small jazz periodical from the late Forties, perhaps Art Hodes’ JAZZ RECORD, of Newton in the basement of an apartment building where he had taken a job as janitor so that he could read, paint, and perhaps play his trumpet in peace.

I think of Django Reinhardt saying, a few weeks before he died, “The guitar bores me.” Did Newton grow tired of his instrument, of the expectations of listeners, record producers, and club-owners? On the rare recording we have of his speaking voice — a brief bit of a Hentoff interview — Newton speaks with sardonic humor about working in a Boston club where the owner’s taste ran to waltzes and “White Christmas,” but using such constraints to his advantage: every time he would play one of the owner’s sentimental favorites, he would be rewarded with a “nice thick steak.” A grown man having to perform to be fed is not a pleasant sight, even though it is a regular event in jazz clubs.

In addition, John Chilton’s biographical sketch of Newton mentions long stints of illness. What opportunities Newton may have missed we cannot know, although he did leave Teddy HIll’s band before its members went to France. It pleases me to imagine him recording with Django Reinhardt and Dicky Wells for the Swing label, settling in Europe to escape the racism in his homeland. In addition, Newton lost everything in a 1948 house fire. And I have read that he became more interested in painting than in jazz. Do any of his paintings survive?

Someone who could have told us a great deal about Newton in his last decade is himself dead — Ruby Braff, who heard him in Boston, admired him greatly and told Jon-Erik Kellso so. And on “Russian Lullaby,” by Mary Lou WIlliams and her Chosen Five (Asch, reissued on vinyl on Folkway), where the front line is bliss: Newton, Vic Dickenson, and Ed Hall, Newton’s solo sounds for all the world like later Ruby — this, in 1944.

In her notes to the Jasmine reissue, Sally-Ann Worsford writes that a “sick, disenchanted, dispirited” Newton “made his final appearance at New York’s Stuyvesant Casino in the early 1950s.” That large hall, peopled by loudly enthusiastic college students shouting for The Saints, would not have been his metier. It is tempting, perhaps easy, to see Newton as a victim. But “sick, disenchanted, dispirited” is never the sound we hear, even on his most mournful blues.

The name Jerry Newman must be added here — and a live 1941 recording that allows us to hear the Newton who astonished other players, on “Lady Be Good” and “Sweet Georgia Brown” in duet with Art Tatum (and the well-meaning but extraneous bassist Ebenezer Paul), uptown in Harlem, after hours, blessedly available on a HighNote CD under Tatum’s name, GOD IS IN THE HOUSE.

Jerry Newman was then a jazz-loving Columbia University student with had a portable disc-cutting recording machine. It must have been heavy and cumbersome, but Newman took his machine uptown and found that the musicians who came to jam (among them Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Hot Lips Page, Don Byas, Thelonious Monk, Joe Guy, Harry Edison, Kenny Clarke, Tiny Grimes, Dick Wilson, Helen Humes) didn’t mind a White college kid making records of their impromptu performances: in fact, they liked to hear the discs of what they had played. (Newman, later on, issued some of this material on his own Esoteric label. Sadly, he committed suicide.) Newman caught Tatum after hours, relaxing, singing the blues — and jousting with Newton. Too much happens on these recordings to write down, but undulating currents of invention, intelligence, play, and power animate every chorus.

On “Lady Be Good,” Newton isn’t in awe of Tatum and leaps in before the first chorus is through, his sound controlled by his mute but recognizable nonetheless. Newton’s first chorus is straightforward, embellished melody with some small harmonic additions, as Tatum is cheerfully bending and testing the chords beneath him. It feels as if Newton is playing obbligato to an extravagantly self-indulgent piano solo . . . . until the end of the second duet chorus, where Newton seems to parody Tatum’s extended chords: “You want to play that way? I’ll show you!” And the performance grows wilder: after the two men mimic one another in close-to-the-ground riffing, Newton lets loose a Dicky Wells-inspired whoop. Another, even more audacious Tatum solo chorus follows, leading into spattering runs and crashing chords. In the out- chorus, Tatum apparently does his best to distract or unsettle Newton, who will not be moved or shaken off. “Sweet Georgia Brown” follows much the same pattern: Tatum wowing the audience, Newton biding his time, playing softly, even conservatively. It’s not hard to imagine him standing by the piano, watching, letting Tatum have his say for three solo choruses that get more heroic as they proceed. When Newton returns, his phrases are climbing, calm, measured — but that calm is only apparent, as he selects from one approach and another, testing them out, taking his time, moving in and outside the chords. As the duet continues, it becomes clear that as forcefully as Tatum is attempting to direct the music, Newton is in charge. It isn’t combat: who, after all, dominated Tatum? But I hear Newton grow from accompanist to colleague to leader. It’s testimony to his persuasive, quiet mastery, his absolute sense of his own rightness of direction (as when he plays a Tatum-pattern before Tatum gets to it). At the end, Newton hasn’t “won” by outplaying Tatum in brilliance or volume, speed or technique — but he has asserted himself memorably.

Taken together, these two perfomances add up to twelve minutes. Perhaps hardly enough time to count for a man’s achievement among the smoke, the clinking glasses, the crowd. But we marvel at them. We celebrate Newton, we mourn his loss.

Postscript: in his autobiography, MYSELF AMONG OTHERS, Wein writes about Newton; Hentoff returns to Newton as a figure crucial in his own development in BOSTON BOY and a number of other places. And then there’s HUNGRY BLUES, Benjamin T. Greenberg’s blog (www.hungryblues.net). His father, Paul Greenberg, knew Newton in the Forties and wrote several brief essays about him — perhaps the best close-ups we have of the man. In Don Peterson’s collection of his father Charles’s resoundingly fine jazz photography, SWING ERA NEW YORK, there’s a picture of Newton, Mezz Mezzrow, and George Wettling at a 1937 jam session. I will have much more to write about Peterson’s photography in a future posting.

One is the best, most jubilant jazz Christmas CD I have ever heard: Mark Shane (and his X-mas All-Stars, including Jon-Erik Kellso) on the Nagel-Heyer label, WHAT WOULD SANTA SAY? It’s a CD I enjoy all through the year.

One is the best, most jubilant jazz Christmas CD I have ever heard: Mark Shane (and his X-mas All-Stars, including Jon-Erik Kellso) on the Nagel-Heyer label, WHAT WOULD SANTA SAY? It’s a CD I enjoy all through the year.