I mean no blasphemy. Jazz fans will understand.

Some time ago, an eBay seller offered an autograph book for sale.

That rather ordinary exterior gave no hint of the marvels it contained: not someone’s schoolmates but the greatest players and singers — of the Swing Era and of all time. Now individual pages are being offered for sale, and I thought that they would thrill JAZZ LIVES readers as they thrill me. The owner of the book was “Joe,” residing in New York City and occasionally catching a band at a summer resort. We know this because Joe was meticulous, dating his autograph “captures” at the bottom of the page. Understandably, he didn’t know much about the lifespan of paper and put Scotch tape over some of the signatures, which might mean that the whole enterprise won’t last another fifty years — although the signatures (in fountain pen, black and colored pencil) have held up well.

That rather ordinary exterior gave no hint of the marvels it contained: not someone’s schoolmates but the greatest players and singers — of the Swing Era and of all time. Now individual pages are being offered for sale, and I thought that they would thrill JAZZ LIVES readers as they thrill me. The owner of the book was “Joe,” residing in New York City and occasionally catching a band at a summer resort. We know this because Joe was meticulous, dating his autograph “captures” at the bottom of the page. Understandably, he didn’t know much about the lifespan of paper and put Scotch tape over some of the signatures, which might mean that the whole enterprise won’t last another fifty years — although the signatures (in fountain pen, black and colored pencil) have held up well.

Through these pages, if even for a moment, we can imagine what it might have been to be someone asking the greatest musicians, “Mr. Evans?” “Miss Holiday?” “Would you sign my book, please?” And they did. Here’s the beautiful part.

Let’s start at the top, with Louis and Red:

This page is fascinating — not only because Louis was already using green ink, or that we have evidence of the band’s “sweet” male singer, Sonny Woods, but for the prominence of trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen. Listening to the studio recordings Louis made while Red was a sideman, it would be easy to believe the story that Red was invisible, stifled, taking a position that allowed him no creative outlet. But the radio broadcasts that have come to light — from the Cotton Club and the Fleischmann’s Yeast radio program — prove that Red was given solo spots during the performance and that he was out front for the first set. Yes, Red had been creating a series of exceptional Vocalion recordings for two years, but I suspect Joe had much to hear on this Saturday night at the Arcadia Ballroom.

Something completely different: composer / arranger Ferde Grofe on the same page with Judy Ellington, who sang with Charlie Barnet’s band:

Time for some joy:

Oh, take another!

Joe really knew what was going on: how many people sought out pianist / arranger / composer Lennie Hayton for an autograph:

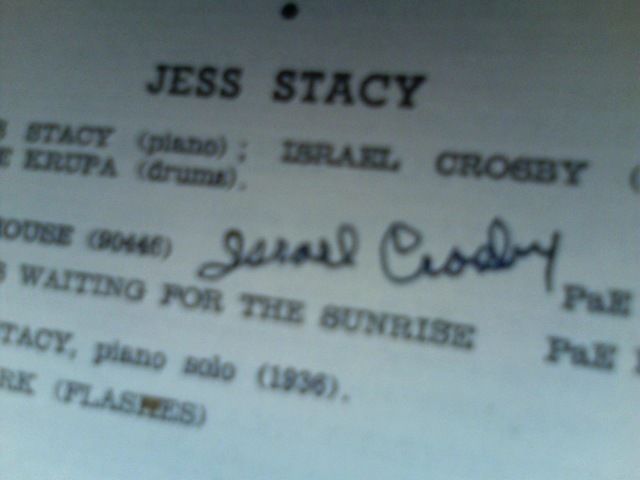

A good cross-section of the 1938 Benny Goodman Orchestra — star pianists Teddy Wilson and Jess Stacy, saxophonists Vido Musso, Herman Shertzer, George Koenig, Art Rollini, as well as the trombonist Murray McEachern, guitarist Ben Heller, arranger Fred Norman, and mystery man Jesse Ralph:

Someone who gained a small portion of fame:

You’ll notice that Joe knew who the players were — or, if you like, he understood that the men and women who didn’t have their names on the marquee were the creators of the music he so enjoyed. So the special pleasure of this book is in the tangible reminders of those musicians whose instrumental voices we know so well . . . but whose signatures we might never have seen. An example — the heroes who played so well and devotedly in Chick Webb’s band: saxophonists Chauncey Houghton, “Louie” Jordan, Theodore McRae, Wayman Carver, bassist Beverley Peer, pianist Tommy Fulford, guitarist Bobby Johnson, trumpeters Mario Bauza, Bobby Stark, Taft Jordan, trombonists Nat Story, Sandy Williams . . . .Good Luck To You, indeed!

But one name is missing — the little King of the Savoy (subject of the wonderful new documentary, THE SAVOY KING — which is coming to the New York Film Festival at the end of September 2012 — more details to come):

Jimmie Lunceford and his men, among them drummer Jimmie Crawford, saxophonist Willie Smith, trumpeter Paul Webster:

saxophonists Joe Thomas and Austin Brown, Jas. Crawford (master of percussion), bassist Mose Allen, pianist Edwin Wilcox, and the little-known Much Luck and Best Wishes:

Blanche Calloway’s brother, the delightful Cab, and his bassist, the beloved Milt Hinton:

trumpeter irving Randolph and Doc Cheatham, drummer Leroy Maxey, pianist Bennie Payne, saxophonists Walter Thomas, Andrew Brown, “Bush,” or Garvin Bushell, and Chu Berry, and Cab himself:

Paul Whiteman’s lead trumpeter, Harry “Goldie” Goldfield, father of Don Goldie (a Teagarden colleague):

I can’t figure out all of the names, but this documents a band Wingy Manone had: vocalist Sally Sharon, pianist Joe Springer, Don Reid, Ray Benitez, R. F. Dominick, Chuck Johnson (?), saxophonist Ethan Rando (Doc?), Danny Viniello, guitarist Jack Le Maire, and one other:

Here are some names and a portrait that would not be hard to recognize. The Duke, Ivie Anderson, Cootie Williams, Juan Tizol, Sonny Greer, Fred Guy, Barney Bigard, Freddie Jenkins, Rex Stewart, and either “Larry Brown,” squeezed for space, bottom right (I think):

And Lawrence Brown, Otto Hardwick, Harry Carney, Billy Taylor, and lead man Art Whetzel:

Calloway’s trombones, anyone? De Priest Wheeler, Claude Jones, “Keg” Johnson, and trumpeter Lammar Wright:

Our man Bunny:

Don Redman’s wonderful band, in sections. Edward Inge, Eugene Porter, Harvey Boone, Rupert Cole, saxophones:

The trumpets — Otis Johnson, Harold Baker, Reunald Jones, and bassist Bob Ysaguirre:

And the trombone section — Quentin Jackson, Gene Simon, Bennie Morton — plus the leader’s autograph and a signature that puzzles me right underneath. Sidney Catlett was the drummer in this orchestra for a time in 1937, but that’s not him, and it isn’t pianist Don Kirkpatrick. Research!:

The rhythm section of the Claude Hopkins band — Claude, Abe Bolar, Edward P. (“Pete”) Jacobs, drums:

And some wonderful players from that band: Joe Jones (guitar, nort drums), trumpeters Shirley Clay, Jabbo Smith, Lincoln Mills; the singer Beverly White (someone Teddy Wilson thought better than Billie), saxophonists Bobby Sands, John Smith, Arville Harris, Happy Mitchner (?); trombonists Floyd Brady and my hero Vic Dickenson, whose signature stayed the same for forty years and more:

I suspect that this triple autograph is later . . . still fun:

If the next three don’t make you sit up very straight in your chair, we have a real problem. Basie at Roseland, Oct. 12, 1937: Earle Warren, the Count himself, Billie, Buck Clayton, and Eddie Durham. The signature of Paul Gonsalves clearly comes from a different occasion, and I imagine the conversation between Joe and Paul, who would have been very pleased to have his name on this page:

Miss Holiday, Mister Shaw, before they ever worked together ANY OLD TIME. I’d call this JOYLAND, wouldn’t you?

And a truly swinging piece of paper, with the signatures of Walter Page, Lester Young, James Rushing, Bobby Moore, Herschel Evans, Ronald “Jack” Washington, Edward Lewis, Freddie Greene, Joe Jones, Bennie Morton . . . when giants walked the earth.

To view just one of these pages and find your way to the others, click here – I’ll content myself with simple gleeful staring. And since I began writing this post, the seller has put up another ten or more — Mary Lou Williams, Ina Ray Hutton, Clyde Hart, Roy Eldridge . . . astonishing!

May your happiness increase.